THE YELLOW JERSEY...

When did it make its first appearance? Who was wearing it? And why yellow? The genesis of the most important prize in cycling in the sporting career of a 20th century hero, Eugène Christophe. In the words of a modern epic poet

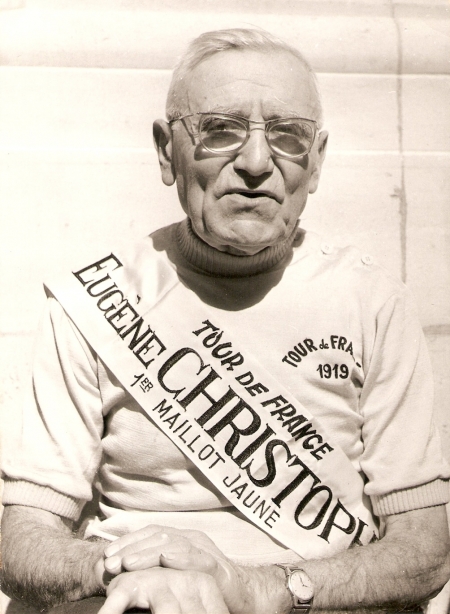

I saw old Christophe again. Eugène Christophe, whose more romantic supporters called “le vieux Gaulois”, the old Gaul, and whom more shameless fans nicknamed “Cri-Cri”, not after a chocolate or a TV series but rather because of his surname or perhaps the sound of a cricket.

In 1913, the vigorous moustached Christophe, who hailed from Malakoff on the outskirts of Paris, wore a hangdog yet light-hearted expression. He was still young: in fact, he was 28. He was also the absolute favourite to win the Tour de France. A year earlier he had won three stages and come second overall. This time, the sixth stage looked likely to be the crowning, make-or-break one: they would race from Bayonne to Luchon, climbing Aubisque, Gourette, Soulor, Tourmalet, Aspin and Peyresourde, across 326 kilometres. On disastrously rough roads.

Christophe was leading the race with his Belgian rival Philippe Thys in mid-descent when, as he said himself “about 10 kilometres outside of Sainte-Marie-de-Campan, I suddenly felt something wasn’t right with the handlebars. I squeezed on the brakes and stopped. I could see that the fork was broken. I can say now that my fork was broken but at the time, I couldn’t say it because it would have been bad publicity for the company I was racing for. So there I was, all on my own on the road. Well, when I say road, I really mean a track. I thought that maybe one of those steep tracks would take me straight to Saint-Marie-de-Campan. But I was crying so hard I couldn’t see a thing. I walked the whole 10 kilometres with the bike over my shoulder. When I arrived in the village, I met a young woman who brought me to the blacksmith on the other side of the village. His name was Monsieur Lecomte. He was very kind and wanted to help me out but wasn’t allowed to. The rules were very strict. I had to do all the repairs myself. I never spent a more complicated few hours in my life than those cruel ones in Monsieur Lecomte’s forge”.

Even a little boy felt sorry for him. His name was Corni – maybe it was a nickname – and he was just seven years old. While Christophe, who right then was aging very quickly indeed, was struggling with hammer and fork, little Corni was blowing up his tyres. The result: a judge called Mouchet – some French names just seem to fit certain faces and expressions - handed Christophe a 10-minute penalty in the classifications, later reduced to three. He was setting an example, said Mouchet, but those minutes would not matter. Because the repairs took more or less four hours and Christophe arrived at Luchon at 20.44, in 29th position. However, he was still ahead of 15 other riders. And he eventually finished seventh in Paris.

Things didn’t go much better for him six year later in the 1919 Tour de France when history repeated itself. Historic races and re-runs, historic cycles and re-cycles. In the penultimate 468-kilometre stage from Metz to Dunkerque, the fork of Eugène Christophe’s bike snapped just a kilometre after he’d passed a bike making workshop. The rules still erred on the side of DIY and the rider doing it all unaided, so Christophe would have to get by on his own. It took him a couple of hours this and he slipped from first to second and then the following day, to third, where he remained. “L’Auto”, the newspaper that organised the Tour, sent him money raised by its readers to refund him his lost prize money. In the end, the sum he received was even larger than Christophe would have earned had he won the Tour: 13,310 francs. With the smallest contribution coming in at three francs and the largest at 500, courtesy of Baron Henri de Rotschild, the list of doners published in “L’Auto”, was as long as a sheet.

But good old Christophe had already set a historic record: he’d taken the first yellow jersey. As time went on, he wore a La Sportive jersey, like many of the riders who were left without a team after the First World War. Alphonse Baugé, a former rider and later sporting director, remarked to Tour patron Henry Desgrange, that if he found it difficult to make out the riders, then it was impossible for the spectators. They needed to at least be able to recognise the classification leader. And in the the fifth Les Sables d’Olonne-Bayonne stage (482 kilometres), Desgrange introduced the yellow jersey, choosing yellow to reference the yellow paper used for “L’Auto”, the newspaper that organised the race. And Christophe, who was leading the classification (and finished third in the final stage) had the honour of wearing it first.

Truth be told, it seems that Christophe didn’t feel very honoured and wasn’t very happy with this particular choice. For a few days, the spectators, jokers that they were, abandoned his romantic name of “le vieux Gaulois” and the light-hearted “Cri-Cri”, and began calling him “Canari” (Canary). Him, a giant, a hero, tour de force of the road…a canary?

But over a century on, I saw old Christophe again. He was finally feeling honoured, happy and even a bit emotional. I saw him at the Santini headquarters. He was looking at the yellow jerseys (and some others besides) that the Italian company makes for the French race. He was looking at them, admiring them, stroking them, patting them. Weighing them in his hands and breathing them in, skimming them with his eyes and lips. Smiling. And, quietly, unbeknownst to anyone, shedding a tear.